You are receiving this because you subscribed to the Behind the Balance Sheet newsletter. This is a new, occasional newsletter, dedicated to the energy transition to accompany a new podcast mini-series. You can unsubscribe without affecting your original subscription.

In this episode in our podcast mini-series, Climate finance expert Huw van Steenis and I interviewed Barry Norris, founder and CIO of Argonaut Capital. Barry has written extensively about why he believes the economics of offshore wind are unsound. He makes some coherent arguments in the podcast and it’s definitely worth listening to if you are interested in this subject.

It’s ironic that our artwork should show Barry alongside a wind turbine! I explore some of the background below.

Barry’s Argument

Barry argues in the podcast that the UK Government target to build 50GW of offshore wind by 2030 is fundamentally flawed. That it’s a waste of money as we already have enough wind power when the wind blows.

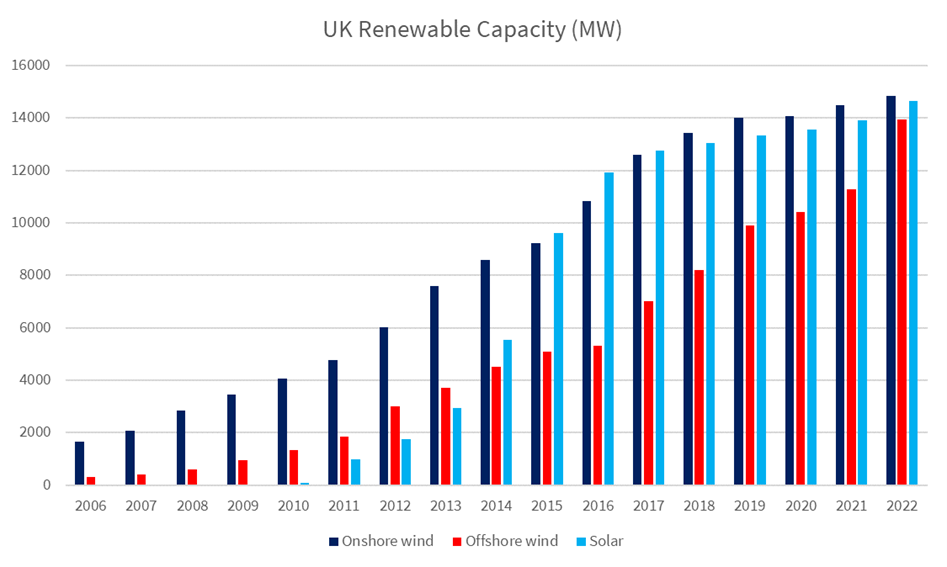

To put this argument in context, we need some data. The first three charts look at the historical picture for wind and solar, as he makes a similar argument against solar.

The first point is that onshore wind farms face planning objections and we already have captured the best sources with the least environmental impact. The first chart shows how onshore wind has grown but we now have similar capacity across onshore wind, offshore wind and solar.

UK Renewable Capacity History

Source Behind the Balance Sheet from Department of Energy Data

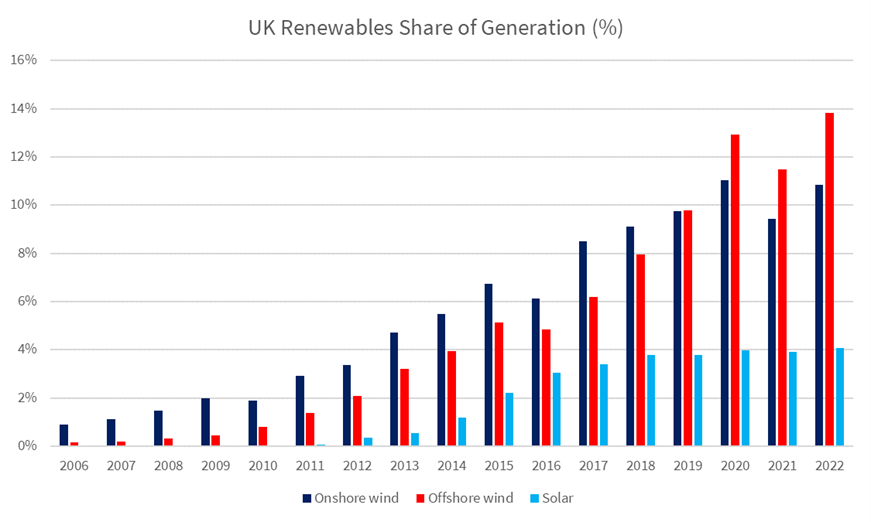

The second chart shows how much more productive the offshore wind has been – from similar capacity, it has overtaken the output of onshore and each dwarfs solar. The UK is not very sunny.

UK Renewable Generation History

Source Behind the Balance Sheet from Department of Energy Data

Renewables have taken share of generation from coal – its share has fallen by more than 20 percentage points over the period. And dirty fuel overall has declined from 44% to 10% of the total.

UK Generation by Fuel Category

Source Behind the Balance Sheet from Department of Energy Data

So that’s the past. Barry’s argument is that we have enough wind now. On windy days, wind can produce near 100% of our power. On still days, it cannot do anything, and we therefore need reliable base power.

The economics are straightforward – gas in the form of CCGT plants are quick to start up and wind down; nuclear is clean but needs to be kept running (both to recover the high capital costs and because technically, you cannot just switch the plant off when the wind starts).

Barry also argues that offshore wind is expensive at a cost of £5m per MW – probably 3 times the cost of a CCGT or more. Hinkley Point is likely closer to £10m per MW but can run virtually 24/7.

Barry argues that we already have enough wind. Here is his breakdown of wind’s market share by half hour periods in the last 3 years:

UK Wind Intermittency

Source: Argonaut Capital

Barry argues that when we have plenty of wind the power price tends to be very low, which is why wind operators need to have revenue guarantees. Here is his table of low power prices in 2021 with the share of wind:

Wind Share on Low Power Price Days

Source: Argonaut Capital

Here is an alternative view of how when it’s windy, power is cheap as there is an excess of supply.

High Wind Supply Coincides with Low Power Prices

Source: Argonaut Capital

Barry argues that there is no point in building masses of extra wind power because when it’s windy, there is a glut of supply. The grid already pays windfarms not to produce on windy days.

The argument therefore is that adding another 35GW of offshore wind will do nothing for electricity capacity on days when there is no wind and will only increase a supply excess when it’s windy.

It’s clear that there is a requirement to have base load capacity and in my view, we need more nuclear if we are to achieve net zero – there is no viable alternative in the UK. How much wind power we need is debatable, and the best/cleanest way forward may well be SMRs.

We have a good discussion on all this in the podcast and I really recommend that you listen in, as Barry explains it better than I can here. One drawback of podcasts, of course, is that you cannot put up a chart; perhaps I should think about using video as this is a subject which probably warrants using that medium.

A Wider Context

To put Barry’s arguments in context, I turned to LCP Delta’s 2023 UK Power Report which contains some useful content to understand the issues. The UK has a target of 50GW of offshore wind by 2030, which is unlikely to be met. We currently have 14GW of offshore wind and an additional 13GW already has a supply agreement. And there is a total of 26GW with connection agreements. Unfortunately, however, only 7GW has planning consent; under 3GW of offshore projects usually receive consent each year, so there is a potential shortfall. These figures exclude the suspension of a major project in Norfolk.

UK Offshore Wind Pipeline

Source: LCP Delta

Cost Pressures

Meanwhile, developers are facing upward pressure on costs. Inflationary increases in materials as well as labour have pushed up installed costs. LCP Delta points to a 35% increase in producer input prices, much higher than consumer price inflation. There is also a much higher borrowing cost to factor in and this is an important element in this type of infrastructure asset. The Global Wind Energy Council suggests that spare capacity in wind energy manufacturing is likely to disappear by 2026.

To counteract this, some commentators have suggested that Government should consider extending the CfD contract length from 15 years to 20-25 years to give investors a longer period of revenue and cash flow. LCP Delta analysis suggests that extending the contract length to 20 years could reduce the ASP by £4/MWh and to 25 years could reduce it by £7/MWh. Of course, this assumes the asset lives will be intact for this period.

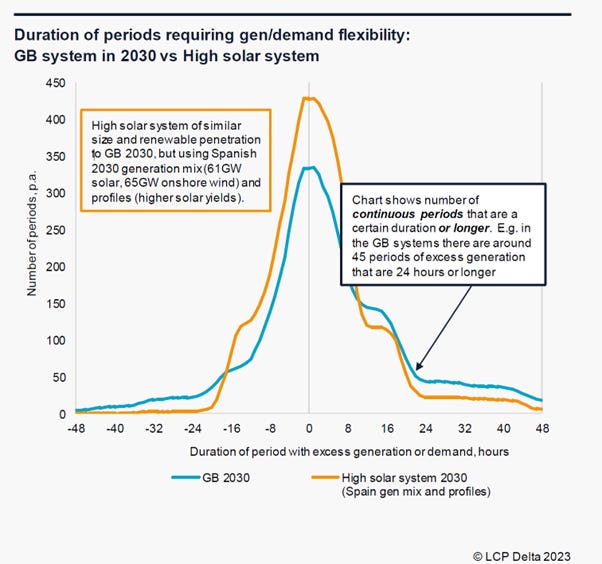

Longer Duration Electricity Storage

An important issue with a growing base of renewables is the lack of long term storage. There are significant peaks and troughs on both the supply side and the demand side. The demand side can be encouraged to shave peaks with flexible pricing. The supply side, however only becomes more volatile as more renewables are added to the mix. This makes long term storage a really desirable facility. Innovative developments like SSE’s water battery are great initiatives but are expensive and limited in scope.

LCP has estimated the proportion of hours across the year that there will be excess renewable (and nuclear) generation on the system - in 2023, only 2% of hours have excess renewables; by 2030 this increases significantly to 60% of hours on their estimates.

During periods where there is not an excess of renewable generation, flexibility can be provided by a variety of sources including low carbon thermal generation, storage discharging, demand reduction and interconnector imports. When there is an excess, the flexibility can come from storage charging, demand turn up, interconnector exports and electrolysis.

Excess Generation in UK

Source: LCP Delta

The consultants compared their projections for Great Britain with Spain where solar is more significant. They estimate that Spain in 2030 will rarely have continuous periods of excess renewable generation or demand that last longer than 24 hours – the sun doesn’t shine for 24 hours but wind can last longer. Hence, Great Britain will likely need more storage of longer duration.

GB Need for Longer Duration Storage

LCP argue that demand will increase by 50% by 2035 and double by 2050, as other sectors decarbonise through electrification and this further increases the need for back-up capacity to ensure security of supply. They estimate that total capital investment (excluding financing costs) required for the construction of new power sector generation and supply-side flexibility assets will reach £430bn in the 2023 to 2050 period.

Electricity Transition Capex

Source: LCP Delta

Conclusion

I don’t pretend to know any of the answers to all of this today. The reason I set out to do the podcast series with Huw was to learn. And what I have learned so far is that this is an even bigger and even more complicated issue than I had thought.

But there is clearly a huge investment opportunity and there are also massive social implications – electricity is a basic human need and we must ensure that it’s affordable. It’s not clear that we are on the right path to achieve that.

As ever, it’s better to listen to the podcast guest than to read my ramblings which are mainly for my own benefit – the guests are much more articulate and can express it better than I can. Let me know what you think.

Still if we create more offshore wind then the UK can become an energy exporter. That will have benefits